The situation…

We’ve all been in the gym before, and in the corner of our eye we see some one doing barbell squats, or deadlifts and you can’t help but look away. It’s clear to even the most untrained eye, that the person has no business playing with barbells yet. Worst of all, it’s not uncommon to see this happening under the guidance of a Fitness Professional/Personal Trainer. Unfortunately, sooner or later, that same person will likely be taking a few months off to see a physio and likely be very put off lifting weights.

What is the underlying cause?

As people become more and more aware of the benefits of ‘strength training’, and ‘free weights’, it’s amazing to see how many more people are jumping into it and giving it a crack. After a quick google, it’s very clear to see that some of the “best” movements for building strength, muscle, and preventing injury as we age are the Squat, Deadlift, Pressing movements, and Pulling movements.

Now I am a MASSIVE advocate for this message- I am in full agreeance. I have seen people go from needing major surgeries to being pain-free through using proper movement and strength training. I’ve coached people who couldn’t get groceries out of their car, through to pulling national record deadlifts. The improvements to their joint health, bone density, strength and wellbeing is truly unbelievable. But on the flip side…. I’ve also met several people who are terrified of squats and deadlifts. They have been seriously injured previously doing movements which were suppose to help them and today I wanted to dive into why I think this happens.

The confusion around strength training and powerlifting

I’ve found when people decide to get into lifting weights, they might do a quick google search on ‘How to squat’ watch a detailed video on barbell squats, and go jump under a bar and give it a crack. I’ve also seen first hand in gyms, clients ask their trainers to teach them how to ‘squat’ and the first thing the trainer does, is walk them over to a squat rack, and chuck some tiny plates on the bar. It is very misunderstood that squatting, deadlift, pressing and pulling are actually all real world primal movements that we do each and every day. These lifts weren’t created in a gym setting for people to do purely with barbells. What I think people fail to realise is, a competition standard squat, press or deadlift are nearly the pinnacle of that particular variation when put on a scale. They are used for lifting as much weight as humanly possible.

There are SEVERAL variations of these movements that are actually easier, safer, and even better at targeting your individual weaknesses/problems than a barbell squat/deadlift etc.

Example of a basic back squat progression model.

Progression, regression, and exercise selection

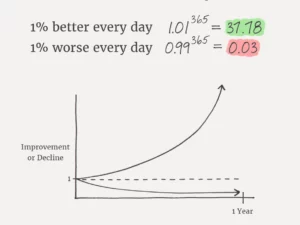

When some body comes to me, the first thing to take into consideration is their goal. For example, I might get a young lifter who wants to get as strong as possible and compete in powerlifting. Does this mean the first thing I’m going to do, is throw the athlete under a bar because that’s what powerlifting is? Absolutely not. Like I said above, the barbell squat is towards the very top end of the spectrum when looking at squat variations on a scale. The first thing I’d do is assess their body weight squat. If there were any issues with that I might use a variation such as a “counter weight squat to a box” to ensure the athlete is able to understand hip hinging, bracing and feeling stable and strong throughout this very basic movement. Once they get the hang of that, I might get them doing a goblet squat until I’m satisfied with their movement and understanding of that slightly more advanced variation. I would continue to work through progressions until I’m certain the athlete is prepared to start training their barbell squat effectively and safely. This process can sometimes be achieved in a day, a month, or a year depending on the individual. This process can’t be skipped, I can guarantee you, if someone can’t efficiently squat with a light dumbbell at their chest – they will have little no benefit trying to push and build their barbell back squat.

For a secondary example, I often get ‘general population’ cliental wanting to lift weights to assist with all the wonderful things I talked about above. Their main focus might be on body composition and trying to address injuries they’ve developed over the years. For several of these people, I may never actually progress them to a barbell deadlift off the floor. Some of them might do trap bar deadlifts, or dumbbell sumo deadlifts. There is technically NO reason for some one to HAVE to do a competition deadlift unless they want to compete in powerlifting or strongman etc. Now don’t take this the wrong way, I’m not at all saying if you don’t compete you shouldn’t do barbell squats, bench press, and deadlifts. I’m simply saying it isn’t a MUST as people seem to think it is. It is highly specific to the individuals goals and needs.

Athlete Prince doing a banded box squat during a rehab phase.

How to practically apply this information to your program

I’d love to sit here and type out every progression, regression, and variation of all the main compound lifts explaining which ones are best for every scenario in a great amount of detail. Unfortunately, that amount of information would easily take up another blog or two.

So instead I will leave you with something else to consider when you are planning your next gym program, for yourself or for your clients. I want you to take a second and consider the overall goal you are trying to achieve. Is it to build muscle? Is it to compete in powerlifting? Is it to bulletproof the body as it ages? Maybe it’s to become a better boxer/fighter?

The truth is, if you can look at your program and explain what each movement is in there for, and what you are trying to achieve by using it – you are leaps and bounds ahead of most already. Take your time and spend 4-12 weeks building and improving these chosen movements until you are satisfied with the result and carry over towards the main goal. You can then decide whether you are going to step up and progress to a harder movement, or if that is even necessary! Maybe you will focus on adding range of movement, stability, or speed to the current variation!

Of course, if there’s any aspect of progression/regression/exercise selection that you would like to better understand, or you are unsure what would best suit you, or your clients, please don’t hesitate to contact me.

Want to work with the Iron Born Team?

Get Started Today